Video Tutorial Modules

In this video I invite you to discover and understand the different module systems in JavaScript.

Why do we need a module system?

When we started writing JavaScript a single file was enough, but very quickly we needed to avoid repetitions. The simplest approach to have reusable code is to inject a variable into the global namespace (window in the case of the browser).

var variable1 = 4

function mySuperFunction () {

// The code of the function

}

window. mySuperFunction = mySuperFunction

In order to avoid that the code of our library overflows on the code of the rest of the application, we will use an IIFE (Immediately invoked function expression). The use of a function makes it possible to limit the scope of the variables (especially at the time when only the keyword var existed).

; (function () {

var variable1 = 4

function mySuperFunction () {

// The code of the function

}

window. mySuperFunction = mySuperFunction

}) ()

This IIFE makes sure that the variables do not overflow, but we can also use it with parameters to define the "dependencies" of our code.

; (function (myFunc) {

console.log ('Here is the result:' + myFunc ())

}) (window.mySuperFunction)

This approach was widely used with jQuery for example.

; (function ($) {

$ ('. demo'). click (function () {

$ (this) .slideToggle ()

})

}) (jQuery)

The limits of this approach

Unfortunately this approach is not extensible and starts to cause problems when you have several dependencies (the files must be included in a specific order). It was therefore necessary to create a system capable of resolving dependencies and organizing the order of execution automatically.

The solutions

CommonJS

The objective of CommonJS was to find a definition format that works with the JavaScript language (without necessarily being constrained to the limitations of browsers). A module is written in the classic way (without IIFE) and will receive an object module which will contain a property exports which will allow you to export what you want.

let count = 0

let step = 1

function increment () {

count + = step

return count

}

function decrement () {

count - = step

return count

}

module.exports = {

increment,

decrement

}

It is then possible to use this module using the function require () to which we will pass the path of our module.

const incr = require ('./ incrementer.js')

const count = document.querySelector ('# count')

document.querySelector ('# increment'). addEventListener ('click', function () {

count.innerHTML = incr.increment ()

})

The system will then take care of automatically including the file and returning what was exported in the return. If there are any sub-dependencies they will be automatically resolved.

This approach was taken by NodeJS and works very well on the server side. On the other hand, it is not possible to use it directly on the browser side and it will require a tool to convert the CommonJS code into browser compatible code. A simple example of an implementation is to create an object to represent the different modules and to encompass the different modules in a function.

modules ('./ app.js') = function (require, module) {

// The code of app.js

const incr = require ('./ incrementer.js')

const count = document.querySelector ('# count')

document.querySelector ('# increment'). addEventListener ('click', function () {

count.innerHTML = incr.increment ()

})

}

This transformation can be done through different tools such as Webpack or ParcelJS.

AMD

Not everyone was satisfied with the direction taken by CommonJS and a group of people decided to develop another module definition system, which would work directly on browsers and support asynchronous loading.

define (('jquery'), function ($) {

return function (selector) {

$ (selector) .click (function () {

$ (this)

.next ()

.slideToggle ()

})

}

})

A module can be named or represent the path of the JavaScript file.

define (('./ cart', './inventory'), function (cart, inventory) {

return {

color: 'blue',

size: 'large',

addToCart: function () {

inventory.decrement (this)

cart.add (this)

}

}

})

The advantage of this approach is that it can be used directly on browsers by setting this function define (you can find more information on the reasons behind this mod system on the RequireJS page).

UMD

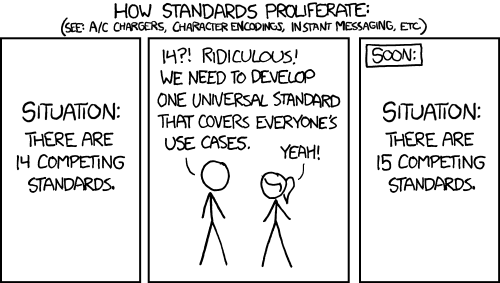

Now we find ourselves with several approaches to define a module and publish a library under these conditions had become problematic.

It is to remedy this problem that UMD (Universal Module Definition) was born. It allows you to define a module that will work with the 3 systems (CommonJS, AMD and window)

; (function (global, factory) {

typeof exports === 'object' && typeof module! == 'undefined'

? factory (exports, require ('react'))

: typeof define === 'function' && define.amd

? define (('exports', 'react'), factory)

: ((global = global || self), factory ((global.ReactDOM = {}), global.React))

}) (this, function (exports, React) {

// Some code

exports.createPortal = createPortal

exports.findDOMNode = findDOMNode

exports.render = render

exports.version = ReactVersion

})

To achieve these ends UMD will add a series of conditions to find out what type of module is used and will inject a parameter exports to the function that will export what must be accessible.

ES205, a standard (ESM)

The solutions seen above are solutions to the absence of a native JavaScript module system. However, with the evolution of standards, JavaScript was equipped with such a system when EcmaScript 2015 arrived.

A script can be loaded into an HTML page as a module.